Fighting for the Future

by Everett Headley

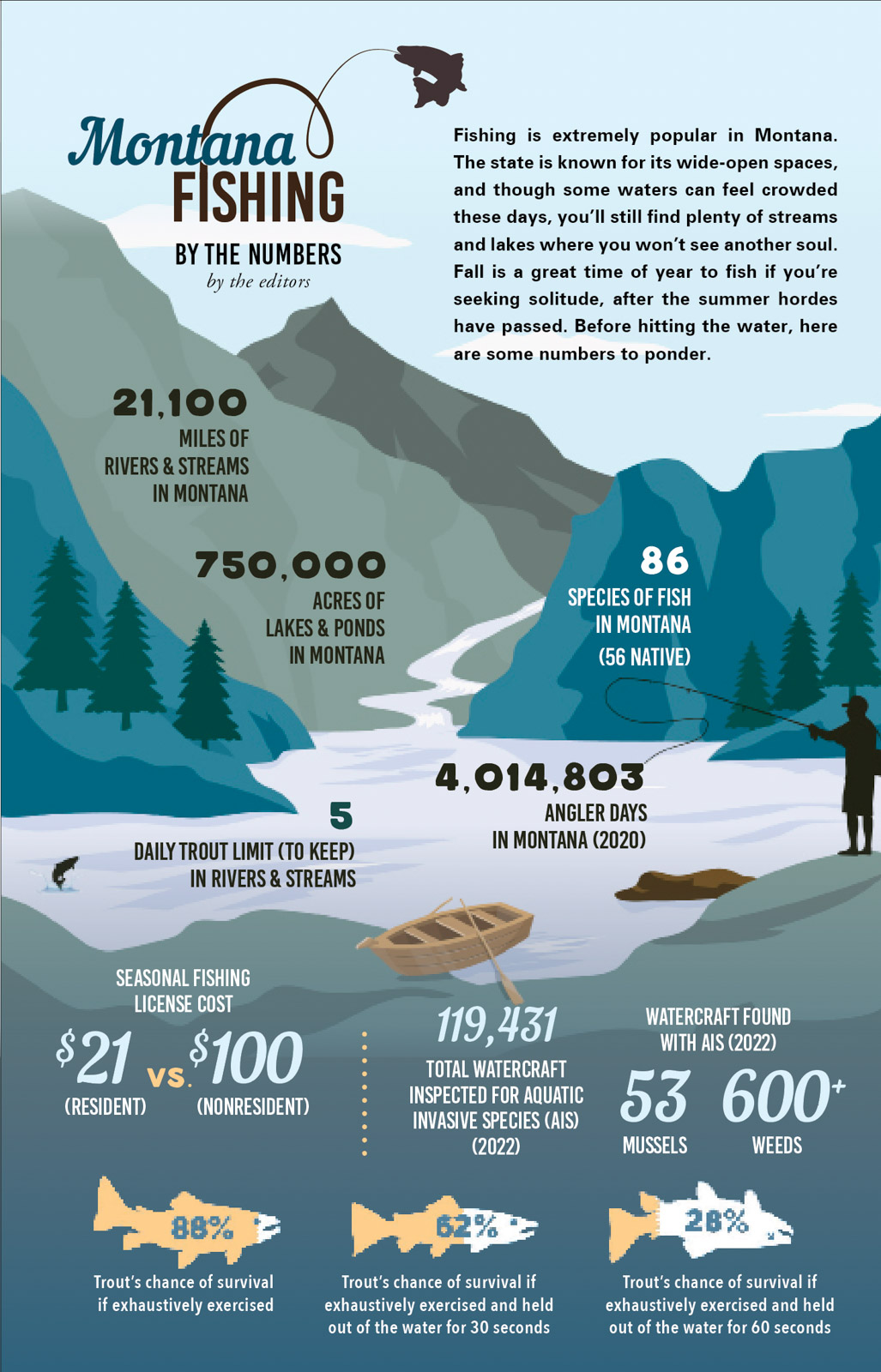

Montana’s majestic fisheries have long inspired anglers worldwide to step into their celebrated waters in search of their own immersive experiences. However, rapidly increasing boats at the launch and waders in the water have intensified angling pressure on already fragile fish battling changing weather patterns and invasive species. Tasked with stewarding these resources, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) works diligently to balance the demands on Montana’s water bodies, while ensuring that they remain healthy and viable aquatic ecosystems. This has become increasingly complex with new threats exposing the fragility of these habitats and inhabitants.

Study Session

Monitoring and analysis projects are conducted year-round across the state. Angler feedback and population surveys guide the department in prioritizing studies and efforts. For example, brown-trout populations are decreasing statewide with no definitive cause. In response, FWP has partnered with the U.S. Geological Survey to research the decline of these otherwise-hearty trout. Eileen Ryce, FWP fisheries chief, is hopeful: “We’re looking for clues, if we had a certain amount of flow, or temperature, or a timeframe that would be able to give the best conditions that will be best for the fish.”

Other stressors contribute to fewer trout in the river. Fish populations in the Beaverhead, Big Hole, Madison, and Ruby rivers are all at an all-time low. Local biologists are discussing catch rates and handling times with anglers, as well as practices to help keep more fish alive after release.

Alien Invasion

Aquatic Invasive Species monitoring is the frontline prevention for threats from outside the state. Its watercraft-inspection program has grown every year and is aided by the Angler AIS Prevention Pass revenue. The $2 ($7.50 for nonresidents) pass is required when purchasing a fishing license and funds inspection sites, education, and fieldwork directly related to keeping Montana waters free of these devastating species.

The FWP AIS page maps current waters and sites being tested and any findings of note. Through the 2023 season, over 90,000 watercraft have been inspected and nearly 20,000 of those were from states deemed “high risk” with known AIS infestations. This dragnet caught 45 mussel-fouled boats. Using high-pressure, high-temperature water, hulls and exteriors are sprayed down and interior compartments are flushed.

Coldwater Collaboration

FWP has a large mitigation program that works across various ownerships to assist struggling fish and their waters. The Future Fisheries Improvement Program (FFIP) is focused on sportfish restoration as well as native nongame species, partnering with landowners to identify possible habitat-recovery programs. While not mandated statutorily, voluntary cooperation is coupled with matching dollars from the community and non-governmental organizations. The results are colder and cleaner water for both landowners and anglers.

Currently, the FFIP is being used to address the warming of the Jefferson and Boulder rivers. Water from tributaries is drawn for irrigation, leaving less and warmer water in the main river. As the area’s lead management biologist, Ron Spoon knows well that solving this pickle will take creative approaches. “These systems were designed around the time of the Civil War and are old and need to be rethought,” he says. “It’s a re-plumbing and it requires overcoming electricity, gravity, and water obstacles.” A trial solution on the Boulder River eliminated three irrigation canals and the installation of pumps. At a cost of $500,000, it kept 65-degree water in the system and pumped 80-degree water into the fields, leaving a net of 7 cubic feet per second (CFS) of cold water instream.

Another problem involves cross-breeding. Warming waters have allowed the expansion of certain non-native species that were originally introduced for sportfishing opportunity. For example, rainbow trout are moving further upstream and hybridizing with westslope cutthroat. These diluted gene pools are often cleared with rotenone and restocked with pure strains to restore the fishery. Bull trout have a similar dilemma, as they cross-breed with encroaching brook trout. Bull-brook hybrids are sterile, however, and the real threat is competition with, and predation by, lake trout and northern pike. In both cases, the solution depends on clear, cold, connected, and complex habitat.

One notable FWP habitat-improvement project is the Marshall Creek Wildlife Management Area near Seeley Lake. Pieced together like a puzzle, with private landowners Plum Creek Timber Company and the Nature Conservancy, along with various grants and further help from the Forest Service Legacy Program, it became the fuel for other restoration efforts. As FWP Region 2 fisheries manager Pat Saffel recalls, “Immediately after removing the fish barriers and culverts, we saw a remarkable increase in redds and spawning activity.”

Wild at Heart

For nearly 50 years, Montana has practiced wild-fish management, “stocking only as necessary.” Non-stocked fish offer a higher-quality experience both on the line and on the plate. What’s more, wild fish have proven to be more resilient to environmental changes and health concerns. If left to their own, they out-reproduce their stocked counterparts. Only in places where reproduction is not enough to maintain the demand for sportfishing—primarily lakes and reservoirs—are fish routinely stocked. And according to FWP, “there is no scenario presented now where we would stock fish in our rivers.”

Access Granted

Access is vital to the future of the state’s fisheries. There will always be a need for additional access and Montana’s Fishing Access Site (FAS) program is unparalleled in the country. Anglers have long paid for this via their license fees, but use by other recreationists has skyrocketed in recent decades. A new requirement that all users of FAS, not just anglers, obtain a conservation license ensures that everyone pays their fair share; it also increases the funding for improving existing sites and establishing new ones. These sites provide great habitat for other animals and are favorite spots for birdwatchers. Families like to picnic and wade-fish at these easy-to-access areas.

Best-Laid Plans

The new Statewide Fisheries Management Plan is far more comprehensive than previous iterations. It includes added information on specific plans, species needs, and pending issues. At nearly 500 pages, it gives detailed information on all of Montana’s fisheries. Publicly accessible fishing-access sites give a good idea of where to start fishing. Populations of species and their distribution through the system help guide anglers to more productive areas, while special management issues raise awareness for conservation-minded fishermen to consider when in sensitive areas. It won’t suggest which fly is working for your time on the water, but some things are better left discovered on one’s own.

Future Fisheries

Despite all these concerns, Montana continues to offer unmatched fishing opportunities—in no small part due to the eternal vigilance and determination on the part of FWP and its team of biologists. Now, as always, anglers who venture here with an elk-hair caddis to entice a cutthroat to rise will find that this is indeed a special place.