Don’t Move a Mussel

by Eli Fournier

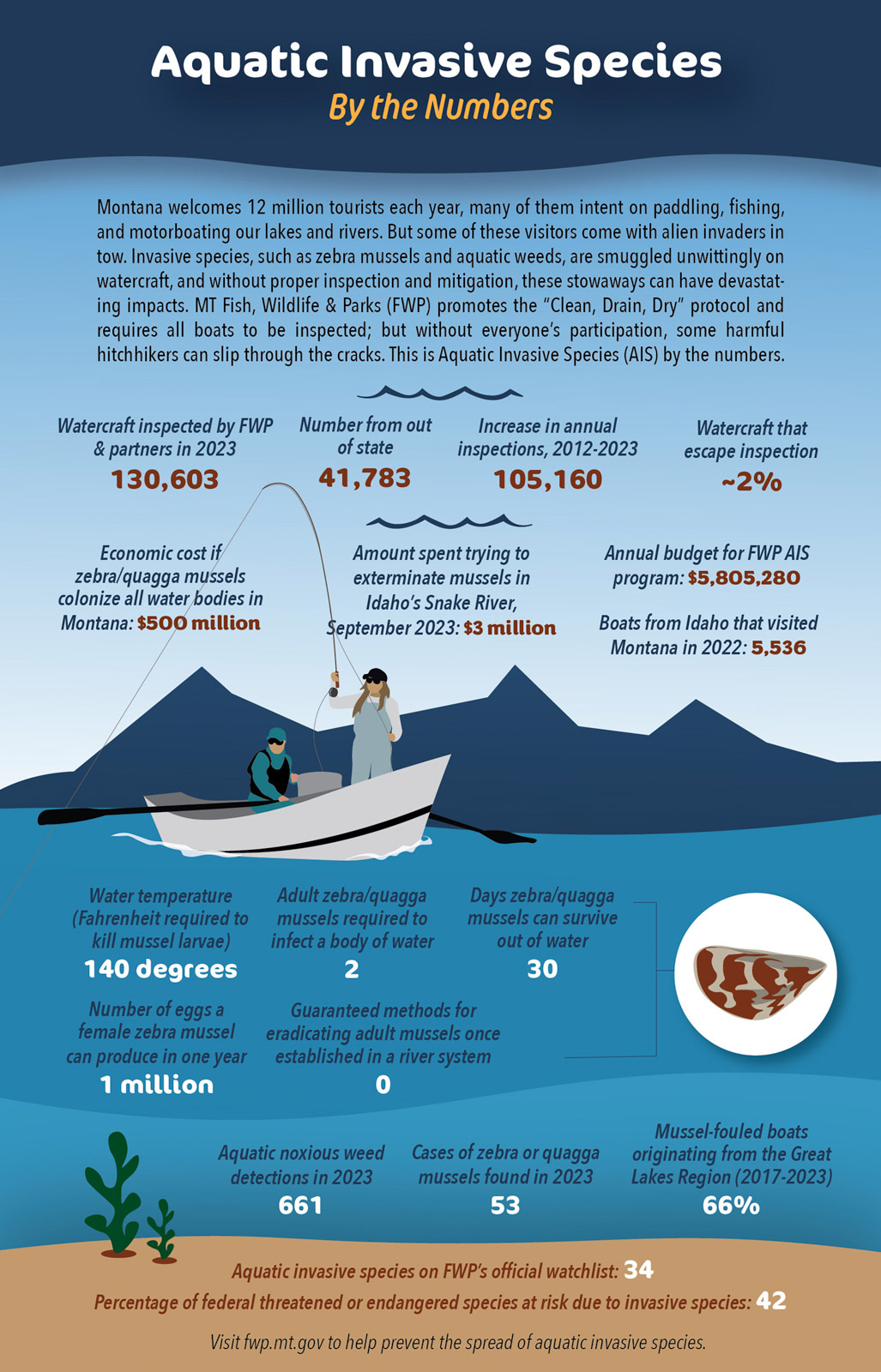

What’s the best way to visualize the number one million? Abstractly, it’s about the population of Montana. In more relative terms, it’s the maximum capacity of 13 NFL stadiums put together, or approximately 40 Montana Griz stadiums full to the brim. It’s also the number of eggs a single female zebra mussel can produce in one breeding event.

Native to Eurasia, these black-and-white stripped mussels are the poster child for Montana’s campaign against aquatic invasive species (AIS), and for good reason. The mollusks are capable of reproducing at a staggering rate, can wreak havoc on waterbodies, and are nearly impossible to eradicate once they’ve taken hold. As such, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks is taking an aggressive approach to the problem—likely the most thorough and effective program in the entire country.

It all starts before anglers even think about dropping their boats in the water. Watercraft entering Montana are required to stop at invasive species checkpoints before launching in any river or lake. In the 2023 boating season, the state inspected 95,298 watercraft at 27 checkpoints, ranging from Broadus all the way to Eureka. In the several-month-long season, the checkpoints stopped a staggering 51 boats fouled with mussels. If that number isn’t shocking, look at it this way: assuming each contaminated boat had 100 mussels (a conservative estimate), and half of those were females, FWP stopped potentially 2.5 billion mussel larvae from being released into Montana waters.

To grasp the enormity of the situation, one must understand what these invasive species do. Mollusks, like zebra and quagga mussels, are filter feeders that eat phytoplankton—tiny, photosynthetic organisms that form the base of the aquatic food web. Phytoplankton are the food source for zooplankton (a wildly diverse group of predatory, planktonic organisms), which in turn feed small fish, arthropods (mayflies, stoneflies, etc.), and so on up the food chain to sport-fish species that anglers like to target. Invasive mussels essentially eat away the base of the food web, potentially causing complete collapse and mass fish die-offs. On top of that, both mussel species love attaching to human-made infrastructure, like pipes, irrigation pumps, headgates, and water-purification systems, where they clog structures in thick mats, causing millions of dollars in damage.

As bad as mussels are, they’re not the only AIS to worry about. Invasive vegetation, like curly-leaf pondweed and hydrilla, can grow in dense patches, choking lakes of oxygen and killing native flora and fauna. Trout, for example, need cool, clear, highly oxygenated water to thrive, and waterbodies damaged by invasive plants can turn too swampy and oxygen-poor to support the species. While aquatic invasives might seem small and insignificant, they have a cascading effect on ecosystems, and can cause adverse impacts far beyond their size.

Perhaps the most difficult part of FWP’s campaign, however, is public outreach. “To me, the big risk right now is out-of-staters coming into Montana, not being aware of the gravity of the threat, not being aware that Montana doesn’t have the mussels,” says Flathead Lake Biological Station assistant director Tom Bansak. “I think there’s a common perception amongst people coming from mussel states that, ‘Oh, these mussels are everywhere. That’s just the way it is.’ Well, that’s the way it is there, but that’s not the way it is here.”

And make no mistake, boaters aren’t the only ones guilty of transporting AIS into the Montana. Wade anglers also need to do their part by decontaminating their waders. FWP offers an easy slogan: “Clean, Drain, Dry.” Wash gear with water 120 degrees or hotter; drain standing water from wading boots, gravel guards, live wells, and boat hulls; and dry equipment with a towel or in the sun. Worthy of particular attention are felt wading-boot soles, which are full of small pores and spaces that invasive vegetation and organisms can squirrel away in. Some states, like Alaska, have banned felt altogether, and Montana might be wise to follow suit. But if you regularly wear felt boots, carry a spare storage tote and a bottle of bleach in your truck, and mix a decontamination solution before hopping large distances between waterbodies.

As AIS become increasingly prevalent in surrounding states, it’s essential to know what to look for and how to deal with invasives. Before taking a fishing trip in Montana, study an ID cheat-sheet online at fwp.mt.gov/conservation/aquatic-invasive-species, and think about printing off a copy to keep in your vehicle or to help educate other anglers. If you need some motivation, just think about that Griz stadium full of zebra mussels—they could be hiding in your boat’s transom right now.