So Long As It Floats

by Emerald LaFortune

Surviving a divorce boat in the winter.

Our green Coleman canoe gets some strange looks at the river access. There’s snow in the forecast for the afternoon, but for now the sun is out and it’s warming up my waders. We pull the canoe down a cutbank and into a small eddy.

“If we tip over here, we just swim back to the car. Right?” I’m joking, but the water is winter-cold and I really, really don’t want to go for a swim in my waders. Two men rigging a spare oar to a shiny RO driftboat look at us with concern as we place a six-pack of beer in the middle of the canoe and charge the nose into the current. One wobbly turn later and we’re moving downstream.

Paddling downstream, we edge the canoe off shallow bars of gravel, giving strainers of piled driftwood a wide berth. We ram the canoe’s nose (sorry, canoe) onto an island.

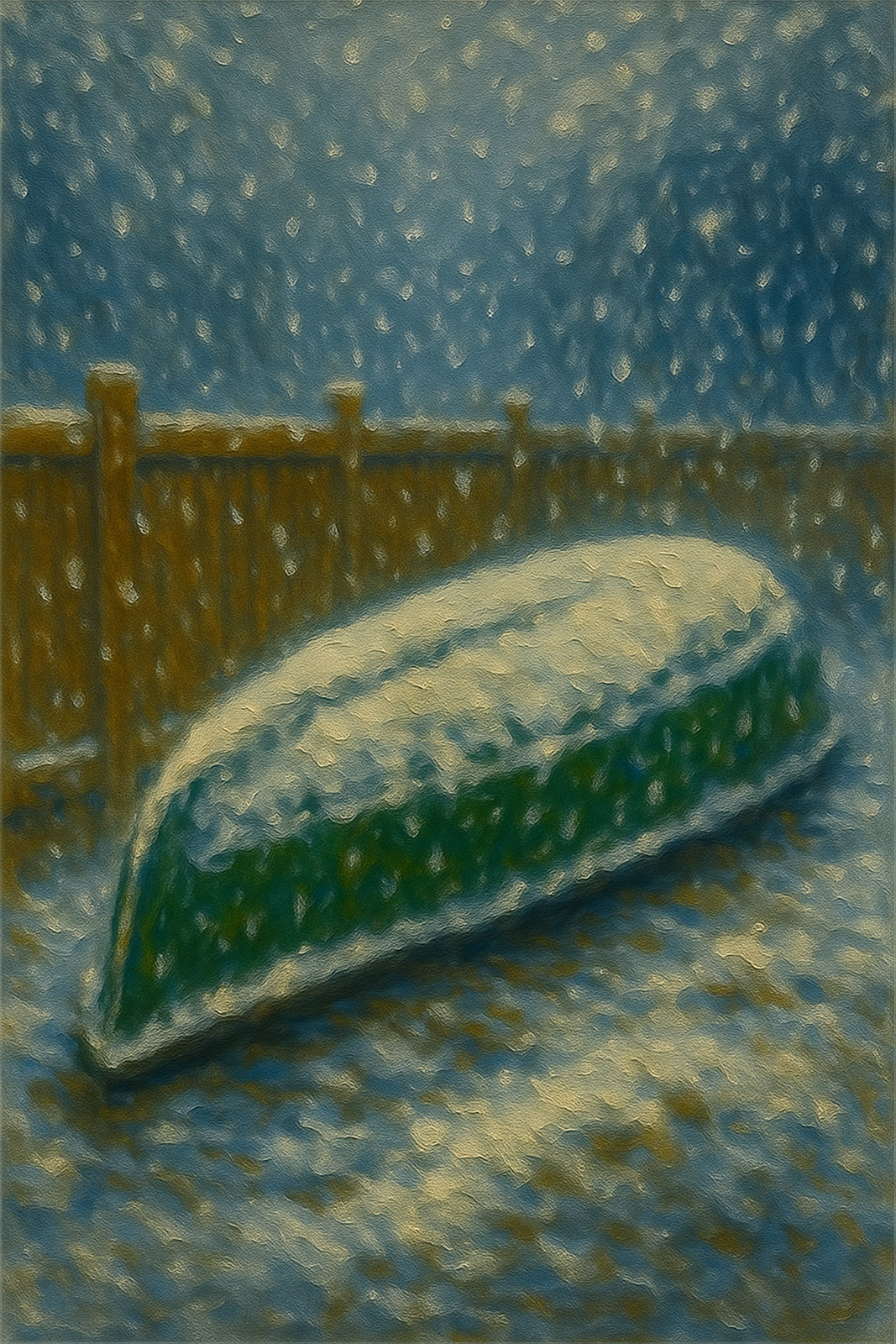

When I guide, I call any double-paddled craft a “divorce boat.” Both my boyfriend and I would rather be unloading a handcrafted driftboat off a custom-welded trailer, but we’re both somewhat broke, a little cocky, and hopelessly, wild-eyed in love with floating on water. We aren’t waiting for the day when we have the best gear. To spend time out here, we use the resources that come cheap and easy, like this canoe, which has been sitting in my backyard abandoned and covered in snow all winter.

“Might as well see if it floats,” Casey said this morning, pushing it over with his foot.

Paddling downstream, we edge the canoe off shallow bars of gravel, giving strainers of piled driftwood a wide berth. We ram the canoe’s nose (sorry, canoe) onto an island. We get out and Casey casts a streamer deep into a run, watching it swing back toward us.

Back in the canoe, we yell at each other a few times (that’s what you do in a duo-paddled bucket that doesn’t turn because it’s designed for lakes). My hands are numb, but I dig in J-strokes as Casey casts another streamer into a frothy eddy. I hear a yelp and watch him fight a thick rainbow. Its scales are just a shade darker than the snowflakes that have started to fall. I smile as I maneuver the canoe back into the current. Now he owes me one.

As the snow begins to dump in earnest, I decide to save my “hold-the-boat-here” card for later. We paddle hard for the take-out, making jokes about taking maidens and furs downstream. We bask in sarcastic mountain-man fantasies and a rainbow-trout high. At the car, we huddle around the heater, thawing our hands and wishing the canoe could put itself back on the roof.

Someday we’ll have a nice driftboat and trailer. Maybe I’ll buy a pair of waders that aren’t hand-me-downs from a fisheries-tech friend. But for now, there’s something scrappy and delicious about these backyard canoes, begged for and borrowed rafts, numb hands, and lunches of dark beer.

Someday we’ll have a nice driftboat and trailer. Maybe I’ll buy a pair of waders that aren’t hand-me-downs from a fisheries-tech friend. Maybe then Casey’s fly rod won’t be the most expensive thing he owns, vehicle included. We both love spending time on rivers more than fancy appliances or Paris vacations, so I know where our first bit of expendable income will go. But for now, there’s something scrappy and delicious about these backyard canoes, begged for and borrowed rafts, numb hands, and lunches of dark beer. I know that in ten years, Casey will feather the oars of our RO driftboat while I catch a rainbow in that frothy eddy. He owes me one after all.

“Remember that time we canoed this stretch in January?” he’ll ask.

“If you’re gonna be stupid, you gotta be tough,” I’ll quote off a beer can.

Then we’ll laugh and hope the river and its trout remember that we came and loved them even before it was easy to do so.